Talking Stories with Mike Fox

- amantineb

- Sep 3

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 5

MIKE FOX, FROM THE HEART INTERVIEW - ’20 Questions’

AMANTINE

A very warm welcome Mike. Thank you for joining me as my very first guest on From the Heart. For those who might not know you yet, you come from a therapeutic background, having worked as a humanistic counsellor, clinical supervisor, and life coach, specialising at various times in alcohol misuse, dementia, and latterly haematological cancer. So it is not surprising that many of your narratives thematically revolve around the idea of selfhood, memory and questions of existence

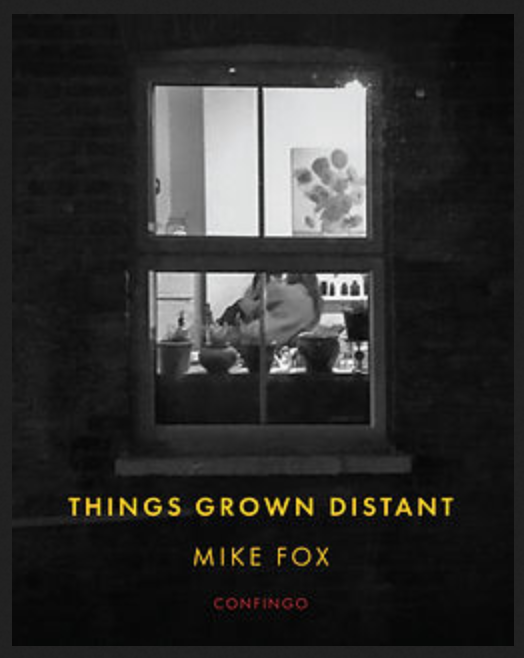

You have been widely published in journals in Britain and elsewhere. Your story The Homing Instinct, first published in Confingo, was selected in Best British Short Stories, published by Salt in 2018. Another story, The Violet Eye, was published in a limited edition by Nightjar Publications, and now you have completed your first short story collection, Things Grown Distant, published by Confingo, with images by Nicholas Royle.

May we begin by my asking you how this collaborative book came about and what has it been like bringing it to fruition?

MIKE

I was invited to submit a manuscript by Tim Shearer, the editor of Confingo. The process took nearly three years, and involved submitting groups of stories until he had chosen the five that comprise the book. Three potential illustrators unfortunately became ill and were unable to complete their part of the work, so Nick Royle kindly stepped into the breach with his photos.

AMANTINE

What is it about the collaborative process you most enjoy.

MIKE

This was not a collaboration as it might normally be described. The idea was that the illustrator, in this case Nick, would provide images that the stories inspired in him. So it wasn’t a case of us putting our heads together, more a conjunction of sensibilities. Tim acted as intermediary.

AMANTINE

How much of your experiences in the field of therapy and counselling informs your literary work?

MIKE

A lot really. Working as a therapist you hear so many speech patterns, verbal mannerisms and vocabularies, which can be helpful when putting together dialogue. There’s also the observation of body language, the sense of how people react to events somatically, and hence the way our physical self can reflect our inner world. You hear life stories, belief systems, told in all sorts of ways. You learn a lot about memory as a phenomenon, and particularly as a layered phenomenon. You meet people speaking from the heart in a very personal and intimate way. All of that is the stuff of fiction.

AMANTINE

How long have you been writing or when did you start?

MIKE

I first started writing stories, and bad poetry, in my teens through to my early twenties. I took it up again in my fifties, so in the latter stage about twelve years, overall something like twenty in terms of fiction. But I also published a book and a lot of journal articles about the various types of therapy work I’d done, almost all about groups of people who’d not previously come to public attention.

AMANTINE

When did you first call yourself a writer?

MIKE

It was a process really. My first story when I returned to fiction won a prize in a small international competition, and then gradually I accumulated other publications. So pretty late in life – later than I would have wished, I eventually felt able to call myself a writer, and someone with a place, however small, within the creative arts. It’s tremendously meaningful for me to think of myself in those terms.

AMANTINE

What first drew you to the short story genre?

MIKE

Reading as a teenager The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog by Dylan Thomas – his storytelling, his characterisation, his humour, the playfulness and poetry in his prose. Immediately I was smitten by the form. There seemed something perfect about it.

AMANTINE

Which occurs first to you— the plot or the characters?

MIKE

I’m unable to plot, so I follow each character’s psychological and emotional process as they respond to the situations in which they find themselves. In that sense I’m learning about them as I write. When it works, and it doesn’t always, I think that approach lends them authenticity – readers are less likely to ask ‘why did they do that?’, even if what they do might not have been easy to foresee.

AMANTINE

What do you look for in your own characters?

MIKE

From the reader’s point of view, that they attract and retain their interest, simply that. For myself, I look for idiosyncrasy, interiority, a sense of humour, amongst other things. Much the same as I’m attracted to in actual life.

AMANTINE

How best would you describe your writing ‘process’?

MIKE

Very slow and, increasingly, tortuous. I re-read a script every time I return to it and amend. I can’t move on until I’m happy with what I’ve already written. I do enjoy the constant editing though – it’s as near as I get to the sort of process I imagine poetry involves. I guess it’s also a sort of diversionary tactic. I‘m usually so short of ideas that it’s easier to concern myself with what I’ve already written than to come up with anything new.

AMANTNE

What constitutes great short story writing for you?

MIKE

A sense of immersion, a sense of discovering characters that I know I must return to. Also, beauty and conciseness in the language. David Wheldon’s The Automaton, John McGahern’s The Conversion of William Kirkwood, and Katherine Mansfield’s The Fly would be examples.

AMANTINE

Who do your regard as your major literary influences and why?

MIKE

Difficult to say really. As mentioned, I love Dylan Thomas’s stories. I wish he’d written more. I read people like Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene and Anthony Powell in my teens, also Scott Fitzgerald, but I don’t know how much of that has seeped in. They were all great storytellers and, even in this day and age, I’m hell-bent on actually telling a story, so I suppose they’ve influenced me in that way.

AMANTINE

What would you have liked to have been told when you started your writing life, that no-one ever told you?

MIKE

I was told that I had aptitude for writing from a very early age. This would have been helpful if I’d also had some practical encouragement. I wish I’d been guided towards someone to show me how it all worked, what the writing life could involve, how to take things forward. I didn’t have a clue.

AMANTINE

Who are the writers you most would like or would have most liked to meet?

MIKE

I dearly love to accost Julian Barnes while he’s doing his crossword on Hampstead Heath, but wouldn’t have the nerve. I actually wrote a story about an imaginary meeting with Dylan Thomas in a Soho pub in the forties. I’d also be fascinated to meet Katherine Mansfield, though I suspect she’d be pretty scary.

AMANTINE

As the spectre of AI looms large over the artistic culture, do you have any thoughts you might like to share on what might be in store for the literary landscape and small presses?

MIKE

Theft and lack of respect, unfortunately.

AMANTINE

What do you like least about writing?

MIKE

Trying to imagine when my imagination isn’t functioning. Submitting stories into what often transpires to be a void.

AMANTINE

What is the most valuable piece of advice you’ve been given about writing?

MIKE

Kevin MacNeil, author of The Brilliant and Forever, very helpfully noticed that my writing can be aphoristic. He encouraged me to continue with that aspect, and said it would help to keep readers loyal. He was right – the aphoristic sentences are the ones readers tend to quote. Other than that, to be more concise and less self-consciously literary.

AMANTINE

Which characters in your stories are most similar to you or to people you know?

MIKE

Reader’s often suspect that my narrators are actually me. God help me if that were the case, but I suppose they are observers, and I am an observer, so we’re similar in that respect. Truthfully, the only characters that I feel have come to life in my stories have been amalgams. Even those who might have their genesis in someone I’ve known will acquire significant additional characteristics during the writing process.

AMANTINE

What advice would you give to a writer working on their first book?

MIKE

Try to do something that instils you with confidence, that bolsters you going forward. Getting one of more stories published first can be a great validation, and can sustain you in moments of doubt. Be discerning regarding the feedback you encounter.

AMANTINE

Do you ever write with an ‘ideal reader’ in mind?

MIKE

No, but I very much write for ‘the reader’, undefined as that person might be. As mentioned, it’s hugely important to feel I’m actually telling a story, which means I often address the reader as I’m writing. I think this can create the sort of intimacy on which the short form, particularly, thrives.

AMANTINE

A topic rarely discussed and one I believe is close to your heart concerns the future of the 'short story' ... care to share your concerns and thoughts?

MIKE

The future of the short story. My impression is that it is becoming increasingly impressionistic/descriptive at the expense of genuine narrative. I feel that if the form strays too far from the sort of story we might have enjoyed as a child it atrophies. I realise I’m likely to be in the minority in suggesting this.

READING FROM THINGS GROWN DISTANT by MIKE FOX

ISBN 978-1-7393745-3-2

CONFINGO PUBLISHING

Photography by Nicholas Royle

Stories by Mike Fox have been nominated for the Best of the Net Anthology 2020, selected for the Best British & Irish Flash Fiction list (BIFFY50) 2019-20. His work was also included in Best British Short Stories in 2018. Nightjar Press published The Violet Eye as a limited edition chapbook. You can read more about Mike Fox on his website

Read a review of THINGS GROWN DISTANT

Comments